Stem Cell Treatment for ACL Injuries

If you’ve ever torn an ACL, or have witnessed an athlete tear an ACL, you know that it is a serious injury.

Aside from the pain and inability to walk properly after the injury, time and physical therapy can be a daunting part of recovery.

It usually takes between 6 – 12 months of recovery and physical therapy to fully heal from a torn ACL. Not to mention wearing a knee brace months after surgery.

What if there was a better way to treat ACL injuries?

Stem cell therapy can be a viable solution and is looking promising.

Stem cell therapy is an emerging form of medicine that uses your bodies natural cells to heal targeted muscles, ligaments,

Although not FDA regulated yet, stem cell therapy is becoming more popular due to its natural, minimally invasive healing process.

Partial ACL Treatment

ACL is the most disrupted knee ligament especially in the young and active. There are about 8.1 injuries for every 100,000 persons per year. About 350000 Americans suffer from ACL injuries and 150000 ACL reconstruction surgeries are performed in the United States every year. The number of ACL injuries is only increasing because:

- A growing number of children and adolescents participating in organized sports

- Increased participation in high-demand sports at an earlier age

- A greater rate of diagnosis

Partial ACL tears are common (ranges from 20–47% of ACL tears) and can progress to complete ACL deficiency, particularly when the amount of ligament tear comprises more than half of its substance.

ACL injuries are graded as follows:

- Grade 1 sprain: the ligament is partially torn, with less than half of the ligament substance disrupted

- Grade 2 sprain: the ligament is partially torn, with more than half of the ligament substance disrupted

- Grade 3 sprain: the ligament is completely torn.

ACL injuries are all too common

AC L tears are associated with injuries to other structures in the knee such as menisci, other ligaments, joint cartilage, and bone. ACL injuries long with meniscal tears frequently occur in athletes. Meniscal tears commonly accompany an ACL injury, and every second acute ACL injury is associated with a meniscal tear. The longer the ACL injury remains untreated, the higher is the risk for meniscal injury in the future. Since significant force is required to create an ACL injury, the articular cartilage of the knee-joint is commonly affected leading to “bone bruising” in 80-90% of cases.

ACL injuries lead to the early development of osteoarthritis

Lack of a functionally normal ACL leads to chronic changes in the static and dynamic loading of the knee. The increased forces on the cartilage and other joint structures result in knee instability and osteoarthritis. Majority of patients with acute ACL tears are younger than 30 years at the time of injury, and many of them younger than 20 years, ACL injuries are responsible for a large number of patients with early onset osteoarthritis. This results in pain and functional impairment in the young or middle-aged adult leading to the “the young patient with an old knee”.

Mechanism of ACL injury

The most common history of an ACL injury may be of a non-contact sudden deceleration or jumping or cutting action. These actions are frequently involving with changing direction. This usually involves rotational maneuvers or lateral bending of the knee into a valgus position [knee is bent inside] with the knee extended [knee is straight and not bent] and the tibia rotated. If the ACL injury results from direct contact, present in about one-third of patients, there is often a history of hyperextension or valgus stress on the knee. A pop is usually heard and/or felt.

Diagnosis of ACL injury

The patient with an acute ACL tear typically presents with pain, knee effusion, hemarthrosis [blood in the knee joint], reduction in knee motion, and difficulty bearing weight. Often a “pop” is heard or felt by the athlete at the time of injury. The patient may not be able to fully flex the knee, but the loss of hyperextension [making the knee as straight as possible] is more indicative of an ACL disruption.

The patient with a chronic ACL tear typically presents with recurrent effusions and the sense that the knee “gives way” or is unstable with attempts at cutting, twisting, or jumping sports.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the primary study used to diagnose ACL injury in the United States. It has the added benefit of identifying meniscal injury, collateral ligament tear, and bone contusions. MRI has a specificity of 95% and a sensitivity of 86% for diagnosing ACL injuries. Direct signs of acute, complete ACL tear are (a) complete discontinuity of fibers or (b) irregular contour with increased signal intensity on water sensitive sequences. MRI signs of partial tears are (a) abnormal intra-ligament signal, (b) bowing of the ligament, and (c) inability to identify all fibers.

Non-Surgical Treatment for ACL injuries

Initial non-surgical treatment includes rehabilitation program [ three-stage progressive program: acute, recovery and functional phases] aimed at improving strength and balance along with bracing. However, when this approach was used in one study in patients with isolated ACL injury, only 31% of patient had excellent to good results when followed for 38 months and 35% of patients in this study eventually required surgical reconstruction. Improper treatment for ACL injuries leads to the development of early osteoarthritis of the knee in the future.

Surgical Treatment for ACL injuries

Patients who fail conservative therapy are usually referred for surgical options. Surgical treatment for ACL rupture initially started with a simple repair using suturing. It progressed to suturing along with some sort of augmentation. Currently, it has evolved to ACL reconstruction, which uses a substitute graft of tendon or ligament fixed into position in pre-prepared drill holes. Three types of grafts are commonly used: those from the patient’s body (autograft), cadaveric human donors (allograft) or a synthetic ligament substitute. For the autograft, the hamstring tendons of semi-tendinosus and gracilis are harvested from the limb of the ruptured ACL and this graft is used during the reconstruction operation. Alternatively, a bone-patella tendon-bone (BPTB) construct uses a section of the middle of the patella (kneecap) tendon with bone at either end. ACL reconstruction is increasingly performed as an arthroscopic procedure.

Evidence for Surgical Treatment for ACL injuries

Suturing of the ACL tear was done in the past. Evidence for this treatment was not flattering. According to one review by Taylor et al, there was a high failure rate, a requirement for additional surgery, and another surgery involving revision for instability. A subset of patients, however, achieved good to excellent subjective and objective long-term outcomes.

Fortunately, ACL injury surgery has evolved into repair and reconstruction. One systematic review by Rodriquez-Merchan revealed that autografts yielded better results than allografts. There was no difference between early and delayed reconstruction. 82% of patients were able to return to some kind of sport participation. 28% of patients presented radiological signs of osteoarthritis with a follow-up of a minimum 10 years.

Another systematic review compared surgical reconstruction of ACL injuries with non-surgical care and found that there appears limited evidence to suggest a superiority between reconstruction versus non-surgical management in functional outcomes. They hence concluded that the current evidence would indicate that patients following ACL rupture should receive non-operative interventions before surgical intervention is considered. However, they also commented that the methodological quality of the literature that they reviewed was poor.

Another study showed that irrespective of treatment [surgery or non-surgical care], patients with ACL injury had a high rate of osteoarthritis. In this study, 41% of patients who had an ACL injury developed moderate osteoarthritis of the knee after 14 years. Conversely, in the control group, who did not have an ACL injury, only 4% developed osteoarthritis. Unfortunately, surgical repair of the ACL injury does not seem to prevent osteoarthritis.

Based on the literature, we can conclude that:

- ACL reconstruction seems to be a better option than simply repairing the ACL tear with a suture

- Although ACL reconstruction is the current standard of care, some patients do not benefit from it

- ACL reconstruction does not seem to prevent the development of osteoarthritis in these patients

Stem Cell Therapy for ACL injuries

Although rightfully, ACL surgery is currently the standard of care [especially when conservative care fails], it does have limitations. It is not universally successful and does not appear to prevent osteoarthritis in the future. This has led to a search for better options to treat these injuries.

The ACL is incapable to regenerate itself after an injury. Hence, stem cell infiltration of the injured ACL probably has an important role. The main mechanism of action of stem cells is converting the hostile environment [catabolic] in the joint to a normal [anabolic] joint. They achieve this by secreting amazing healing and growth factors which are anti-inflammatory and aid in repair. These factors also stimulate the native stem cells to cause some regeneration. This results in pain relief and improvement in function.

Read more about the benefits of stem cell therapy.

PRP injection of partial ACL tears via Surgical Arthroscopy

Autologous conditioned plasma [ACP] is a type of Platelet rich plasma [PRP]. ACP has approximately twice the number of platelets [which have a lot of growth factors] compared to whole blood and also has plasma which has numerous growth factors. Koch et al, injected ACP, using arthroscopic guidance in twenty-four patients (mean age 41.8 years) who were affected by partial rupture of one or both ACL bundles. These patients were followed for about 25 months. They reported encouraging data. The failure rate (persisting knee instability) was only 12.5%. Objective tests measuring knee instability showed significant improvements. Return to sport practice was achieved after mean 4.8 months. They concluded that this technique provided promising results at mid-term follow-up to treat partial ACL lesions.

The same group published another study in which 42 patients with partial ACL tears were injected again with ACP using arthroscopy. The patients were reevaluated after 33 months. The failure rate was only 9.5%. Improvements in knee stability, pain scores and function were noted. Return to sport was achieved after an average of 5.8 months in 71.1% of the patients. The authors concluded that “this new treatment option revealed in midterm follow-up promising results to treat partial ACL lesions with a reduced need for conversion to ACL reconstruction and with a high percentage of return to pre-injury sport activity”.

There are no studies reporting the ACL injection of stem cells using an arthroscope. However, since stem cells are known to have significantly higher anti-inflammatory and regenerative effects than ACP, it is possible that stem cells may have better results than ACP in this setting.

Stem Cell Treatment for ACL injuries with injections without Surgery

Centeno et al reported a case series in which ten patients with grade 1, 2, or 3 ACL tears with less than 1 cm retraction in the subacute phase [average time from injury to treatment was 3.45 months]. These patients were treated with fluoroscopic percutaneous ligament infiltration and intra articular injection [no surgery] with patients’ own bone marrow stem cells [which are FDA allowed], PRP and platelet lysate. The median time of follow up was 6 months. Most patients reported improvement in pain and functional scores. Significantly, a majority of patients exhibited positive changes in the follow-up MRI’s reflecting regeneration of the ACL. The authors concluded that although more research is required, percutaneous BMC treatment of ACL injuries may be promising.

The same group published a second study of 23 patients with similar ACL injuries and the same treatment protocol as described above. The mean time from injury to treatment was 22.6 weeks. This time the follow-up period was longer up to 23 months. Decreases in pain scores and improvements in functional scores were noted. When MRI was repeated after an average duration of 8.7 months, positive changes in the ACL were seen, suggesting regeneration. Only 17% of patients eventually required surgery. There was a relatively low rate of patients opting for ACL reconstruction surgery and the low re-tear rate suggesting that this treatment with stem cells is very encouraging.

Evidence for Stem Cell Treatment for ACL injuries

The conclusion for the evidence for stem cell treatment for ACL injuries is

- Although limited, the evidence for stem cell treatment for ACL injuries is compelling

- There is evidence that it provides pain relief, improves function and return to play

- There is evidence of regeneration based on follow-up MRI

The development of osteoarthritis is very common in patients who injure ACL. However, we still do not know if stem cell treatment for ACL injuries prevents osteoarthritis in these patients.

This an X-ray image of ACL stem cell procedure

Conclusion

ACL injuries are very common in active individuals and there is an increase in the incidence probably from increased sports participation and having access to a better means for diagnosis. Having failed conservative therapies like PT, most undergo surgical reconstruction which can have failure rate but does not prevent the progression of joint arthritis. Biologics like PRP and stem cell, although still in infancy, may have an important role to fill this void as the percutaneous procedures are less invasive, known to regenerate tears. This seems to be a good option prior to trying surgical options. Patients who fail stem cell treatment for ACL injuries can always try surgical options. Unfortunately, vice versa is not possible.

Word of caution: There are a lot of “scam” stem cell clinics who charge desperate patients very high costs. Do you research before you sign up for stem cells.

Carole is an example of how successful knee stem cell injections are in relieving pain and improving lives. She had many structures of her knee injected including ACL.

How to treat ACL injuries and ACL tears?

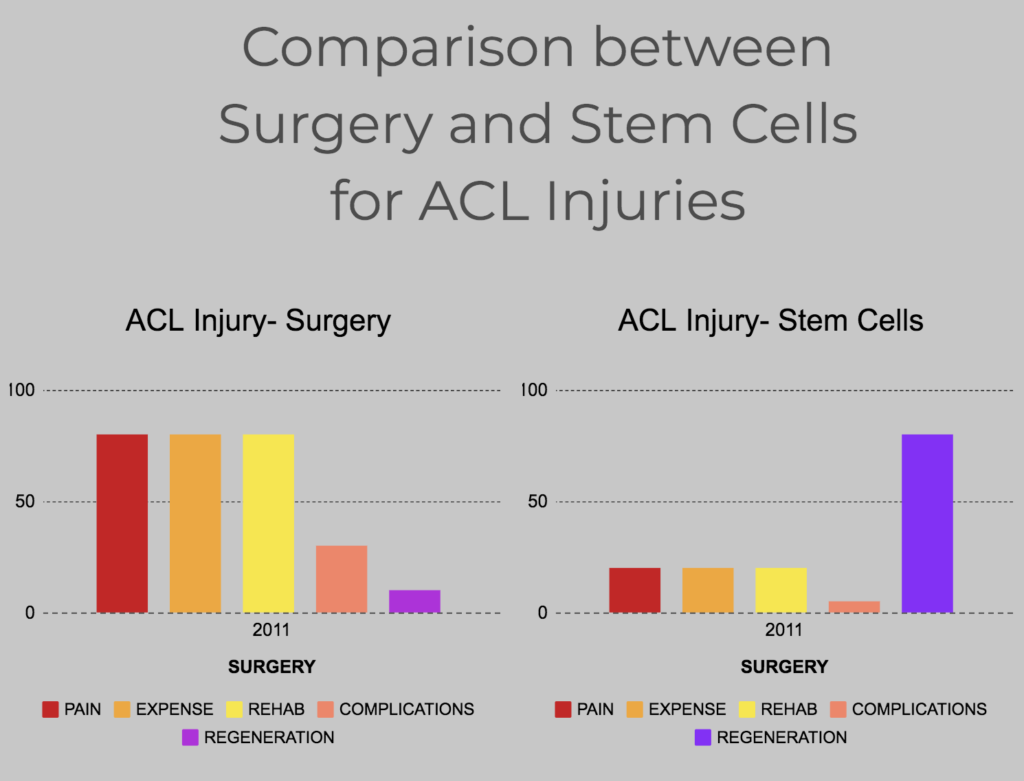

Surgery is currently the standard of care. However, it is invasive, expensive, need extensive rehabilitation and most importantly does not prevent the development of osteoarthritis in the future. Compared to surgery, Stem cells are less invasive, clearly not as expensive with less rehab and should be strongly considered before surgery. Most importantly, we now have evidence that stem cells can regenerate the injured ACL.

Below is the video of Carole who has ACL degeneration treated with stem cells. She also had osteoarthritis of the knee which was addressed successfully with stem cells.